Designs for non-normal Endpoints with approximately normal test statistics

Source:vignettes/other-endpoints.Rmd

other-endpoints.RmdCurrently, adoptr supports the optimization of adaptive

two-stage designs with either normally or t-distributed test statistics.

More specifically, it is required that the first stage test statistic,

and the distribution of the second stage test-statistic conditional on

the first-stage test statistic, is either normal or t-distributed.

When individual observations are normally distributed, stage-wise Z- or T-test statistics fulfill these criteria. In practice, however, there are many situations where one cannot reasonably assume that individual observations are sampled from a normal distribution. It is common for trials to be conducted for binary or time-to-event endpoints, e.g. if one is interested in investigating the impact of a drug on mortality. One way to deal with this situation is by transforming the data to a test-statistic which is approximately normal. In the following, we will explain how to do so for binary and for time-to-event endpoints.

We will be using the following notation:

- \(X_i^T\) will denote an observation of recruit \(i\) in the treatment arm

- \(X_i^C\) will denote the observation of recruit \(i\) in the control arm

- \(n\) will denote the group-wise sample size.

Binary endpoints

Binary endpoints are endpoints where individual observations follow a Bernoulli distribution, i.e. \(X_i^T \sim Bin(1,p_T)\) and \(X_i^C\sim Bin(1,p_C)\). Our goal is to compare the probability \(p_T\) of an event in the treatment group with a fixed value (single-arm trial) or with the probability \(p_C\) of an event in the control group (two-armed trial). Thus, assuming that larger probabilities are favorable, we have

\[ H_0: p_T \leq p_C\quad \text{vs.} \quad H_1:p_T > p_C. \]

To test this hypothesis, one could use the test statistic \[ U=\sqrt{\frac{n}{2}}\frac{\hat{p}_T-\hat{p}_C}{\sqrt{\hat{p}_0(1-\hat{p}_0)}}, \]

where \(\hat{p}_T=\frac{1}{n}\sum_i^{n}X_i^T\) and \(\hat{p}_C=\frac{1}{n}\sum_i^{n}X_i^C\) are the maximum likelihood estimators of \(p_T\) and \(p_C\) and where \(\hat{p}_0=\frac{\frac{1}{n}\sum_i^{n}X_i^T+\frac{1}{n}\sum_i^{n}X_i^C}{2}\).

The outcome of \(U\) is then compared to \(c_f\) and \(c_e\), the first stage boundaries. If \(U\in [c_f,c_e]\), we continue the trial and compute a new value for \(U_2\) in the second stage, where we reject the null if \(U_2>c_2\).

It is a well-known fact that this test statistic is asymptotically normal, and we will give a proof of this in the next section.

Asymptotic distribution of the test statistic

We begin with the difference \(\hat{p}_T-\hat{p}_C\). Using the de Moivre-Laplace theorem, we get that \[ \frac{n\hat{p}_T-np_T}{\sqrt{n}} \overset{d}{\to} \mathcal{N}(0,p_T(1-p_T)). \] After defining \(\sigma_A^2=p_T(1-p_T)+p_C(1-p_C)\), we obtain \[ \frac{n\hat{p}_T-np_T}{\sqrt{n}}-\frac{n\hat{p}_C-np_C}{\sqrt{n}}=\sqrt{n}(\hat{p}_T-\hat{p}_C-(p_T-p_C))\overset{d}{\to}\mathcal{N}(0,\sigma_A^2), \] so it follows \[ \sqrt{n}(\hat{p}_T-\hat{p}_C)\overset{d}{\to}\mathcal{N}(\sqrt{n}(p_T-p_c),\sigma_A^2). \] Applying the continuous mapping theorem, it results that \(\hat{\sigma}_0:=\sqrt{2\hat{p}_0(1-\hat{p}_0)} \overset{P}{\to}\sqrt{2p_0(1-p_0)}:=\sigma_0\), so by Slutzky’s theorem, we get \[ \frac{\sqrt{n}(\hat{p}_T-\hat{p}_C)}{\sigma_0}=\sqrt{\frac{n}{2}}\frac{\hat{p}_T-\hat{p}_C}{\sqrt{\hat{p}_0(1-\hat{p}_0)}}\overset{d}{\to}\mathcal{N}\left(\sqrt{n}\frac{p_T-p_C}{\sigma_0},\frac{\sigma_A^2}{\sigma_0^2}\right). \] Hence, for sufficiently large \(n\), \(U\) is approximately normal.

Note that under the null hypothesis, \(\sigma_A^2=\sigma_0^2\) and \(p_T=p_C\). Thus, approximately, \(U\sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)\) under \(H_0\).

adoptr and binomial endpoints

Implementation details

Currently, adoptr only supports the specification of a

single fixed reference value fo \(p_C\), while general prior distributions

are supported for the effect size \(\theta\).

This is a limitation, as uncertainty about the control group rate cannot be represented in this framework. However, in a trial comparing a new treatment to an existing one, it is usually reasonable to assume that some information about the event rate in the control group is available beforehand.

Example

Assume we want to plan a two-armed trial with an assumed rate of

events in the control group of \(p_C=0.3\). These parameters are encoded in

the DataDistribution object.

datadist <- Binomial(0.3, two_armed = TRUE)Let us furthermore postulate a normal prior distribution for \(\theta\) with expectation \(\mu=0.2\) and standard deviation \(\sigma=0.2\), which was truncated to the interval \((-.29,0.69)\). It is necessary to use a truncation to ensure that \(p_T \in (0,1)\).

H_0 <- PointMassPrior(.0, 1)

prior <- ContinuousPrior(function(x) 1 / (pnorm(0.69, 0.2, 0.2) -

pnorm(-0.29, 0.2, 0.2)) *

dnorm(x, 0.2, 0.2),

support = c(-0.29,0.69),

tighten_support = TRUE)We require a maximal type one error of \(\alpha\leq 0.025\) and a minimum expected power of \(\mathbb{E}[1-\beta]\geq 0.8\).

alpha <- 0.025

min_epower <- 0.8

toer_cnstr <- Power(datadist, H_0) <= alpha

epow_cnstr <- Power(datadist, condition(prior, c(0.0,0.69))) >= min_epowerNext, we need to choose an objective function, which will be the

expected sample size under the chosen prior distribution for \(\theta\) in this example. After having

chosen a starting point for the optimization procedure, we use the

minimize function to determine the optimal design

parameters.

ess <- ExpectedSampleSize(datadist,prior)

init <- get_initial_design(0.2,0.025,0.2)

opt_design <- minimize(ess,subject_to(toer_cnstr,epow_cnstr),

initial_design = init, check_constraints = TRUE)

plot(opt_design$design)

Time-to-event endpoints

Time-to-event endpoints are another common type of endpoint used in clinical trials. Time-to-event data is two-dimensional and consists of an indicator denoting the occurrence of an event or censoring, and a time of the event or censoring.

A common effect measure for time-to-event endpoints is the so called hazard-ratio, which is the ratio of hazard functions between two groups or the ratio of the hazard of one group and a postulated baseline hazard.

In the following, the hazard ratio will be denoted by \(\theta := \frac{\lambda_C(t)}{\lambda_T(t)}\), and we will assume that \(\theta\) is constant over time. Assuming that less hazard is favorable, the resulting hypotheses to be tested are

\[ H_0: \theta\leq 1 \quad \text{vs.} \quad H_1: \theta >1. \]

Let \(1,\dots,J\) be the distinct times of observed events in either group and let \(n_{T,j}, n_{C,j}\) be the number of subjects, who neither had an event nor have been censored. Additionally, let \(O_{T,j},O_{C,j}\) denote the observed number of events at time \(j\). In the following we assume that there are no ties, so \(O_{T,j},O_{C,j}\in \{0,1\}\). Define \(n_j:=n_{T,j}+n_{C,j}\) and \(O_j:= O_{T,j}+O_{C,j}\). Under the null, the hazard functions of the groups are equal. Thus, for \(i \in \{T,C\}\), \(O_{i,j}\) can be regarded as the number of events in a draw of size \(n_{i,j}\), where the population has size \(n_j\). Therefore, \(O_{i,j}\) follows a hypergeometric distribution, i.e. \(O_{i,j}\sim h(n_j,O_j,n_{i,j})\). This distribution has an expected value of \(E_{i,j}:=\mathbb{E}[O_{i,j}]=n_{i,j}\frac{O_j}{n_j}\) and variance \(V_{i,j}:=\text{Var}(O_{i,j})=E_{i,j}\left(\frac{n_j-O_j}{n_j}\right)\left(\frac{n_j-n_{i,j}}{n_j-1}\right)\). Using these definitions, we can define the so-called log-rank test statistic as

\[

L=L_T:=\frac{\sum_{j=1}^J O_{T,j}-E_{T,j}}{\sqrt{\sum_{j=1}^J V_{T,j}}}.

\] Note that it does not matter whether we consider \(L_T\) or the analogously defined statistic

\(L_C\), both of them yield the same

results, so we abbreviate \(L_T\) to

\(L\). By the central limit theorem, it

is easy to see that \(L \overset{d}{\to}

\mathcal{N}(0,1)\). Under the alternative, it can be shown that,

approximately, \(L \sim

\mathcal{N}(\text{log}(\theta)\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{J},1)\). If \(\psi\) is the average probability of an

event per recruit in both arms (also known as the event rate), \(J\) can be replaced by \(2 \cdot n \cdot \psi\) (where \(n\) denotes, like in the previous sections,

the number of recruits per group). Thus, by by postulating an event

probability, we can calculate the number of recruits per groups that

would be required to achieve a specific number of events, and by

extensions, a specific power. In adoptr, the parameter

\(\psi\) needs to be pre-specified in

order to obtain a one-parametric distribution (the other parameter being

\(\theta\)), and \(\psi\) is assumed to be fixed over time.

This is similar to the case of binary endpoints, where the response rate

in the control group \(p_C\) had to be

a constant value.

Survival analysis and adaptive designs

Notation

We expand the previous notation by an index \(k\in \{1,2\}\) denoting the current stage. We observe \(d_1\) events until the interim analysis at times \(\{1,\dots,J_1\}\), and we observe \(d_2\) events in total until the final analysis at times \(\{1,\dots,J_2\}\). We stress that, in this notation, \(d_2\) denotes the cumulative number of events in both stages. Furthermore, let \(O_{i,j,k}\) be the number of observed events in arm \(i\in \{T,C\}\) at time \(j \in \{1,\dots,J_k\}\) in stage \(k \in \{1,2\}\). Like in the previous section, let \(E_{i,j,k}= \mathbb{E}[O_{i,j,k}]=n_{i,j,k}\frac{O_{j,k}}{n_{j,k}}\), where \(n_{i,j,k}\) is the number of patients that have not had an event until the end of stage \(k\), and let \(O_{j,k}=O_{T,j,k}+O_{C,j,k}\) and \(n_{j,k}=n_{T,j,k}+n_{C,j,k}\). Likewise, we can define \(V_{i,j,k}\) analogously to the previous section. The cumulative log-rank test statistic up to stage \(k \in \{1, 2\}\) can then be defined as \[ L_k=\frac{\sum_{j=1}^{J_k} O_{T,j,k}-E_{T,j,k}}{\sqrt{\sum_{j=1}^{J_k} V_{T,j,k}}}. \]

Dependency issues and solutions

For normal distributed endpoints, the stage-wise test statistics come from independent cohorts, which makes the calculation of their joint distributions straightforward.

In survival analysis, it is possible to have patients that have been recruited during the first stage, but have not had an event at the point of the interim analysis. Those provide information for both stages: in the first stage, we know that they survived, and in the second stage, they might die or even survive until the end of the trial. This makes the construction of a pair of suitable test statistics more challenging.

In the following, we will present two methods to avoid these issues.

Solution 1: Independent increments

It can be shown that the statistic \[ Z_2:= \frac{\sqrt{d_2}L_2-\sqrt{d_1}L_1}{\sqrt{d_2-d_1}} \] is approximately distributed according to \(\mathcal{N}(\text{log}(\theta)\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{d_2-d_1},1)\), and that \(L_1\) and \(Z_2\) are approximately independent.

The recruitment and testing procedure is now as follows: During the accrual time, recruit approximately \(\frac{d_1}{2\psi}\) patients per group and conduct the interim analysis after having observed \(d_1\) events overall.

Assume, \(q\) patients have not had an event until the interim analysis. These patients are censored for the computation of \(L_1\). \(L_1\) is then compared to the futility and efficacy boundaries \(c_f\) and \(c_e\), and recruitment is stopped if \(L_1 < c_f\) or \(L_1 > c_e\). If \(c_f \leq L_1 \leq c_e\), recruitment of patients for the second stage will continue.

The number of patients to be recruited in the second stage is calculated so that \(d_2(L_1)\) events are expected to be observed in the second stage. Similarly to the normal case, the required number of events is a function of the first-stage test statistic. The observation of these \(d_2(L_1)\) events will trigger the conduct of the final analysis, where \(Z_2\) is compared to \(c_2(L_1)\).

Solution 2: Left truncation at the second stage

Another approach uses left truncation and right censoring. In the following, \(R_i\) stands for the calendar time of entry for individual \(i\). Furthermore, let \(T_i\) be their time from entry to the event and \(C_i\) their time from entry to censoring. Assume that these values are independent and let \(r_i,t_i,c_i\) be realizations of \(R_i,T_i\) and \(C_i\). Additionally, we denote the calendar time of the interim analysis by \(t_{Int}\) and the calender time of the final analysis by \(t_{Fin}\).

Let individual \(i\) be recruited before the interim analysis. Define \(y_{i,1}:=\min \{t_i,c_i,t_{Int}\}\), i.e. \(y_{i,1}\) can be interpreted as the minimum time until “something” happens to individual \(i\) in the first stage (either the interim analysis is conducted, \(i\) had an event or they were censored). The risk interval for the first-stage test statistic is now defined to be \((0,y_{i,1})\), which means that individual \(i\) belongs to the risk set at the event time \(t_j\) if \(\min \{c_i,t_{Int}-r_i\}\geq x_j\).

If \(i\) has not had an event yet in the first stage, was not lost to follow-up yet in the first stage, or if they were recruited in the second stage, we define \(y_{i,2}:=\min\{t_i,c_i,t_{Fin}\}\). As before, \(y_{i,2}\) can be interpreted as the minimum time until something happens to individual \(i\) in the second stage: Either the final analysis is conducted, \(i\) had an event or was censored. The risk interval for an individual \(i\) for the second stage test-statistic is then defined as \((\max(t_{Int}-r_i, 0),y_{i,2})\). This definition takes into account that that a patient \(j\) who was recruited in the first stage, but had no event until the interim analysis, has already provided the information of “no event” in the time span \((0, t_{Int}-r_i)\) for the interim analysis. To avoid double-counting in the second analysis, we say that this patient is not in the risk set until this time span is over.

Using this idea, one can conduct the analyses of the trial according to the following instructions: For the interim analysis, the procedure is the same as for the independent increment solution, i.e. \(L_1\) is computed in the usual way and compared to the futility and efficacy boundaries \(c_f\) and \(c_e\). If \(L_1 \in [c_e,c_f]\) (i.e. the trial is not stopped for early efficacy or futility), we continue the observation and recruit new patients, such that \(d_2(L_1)\) events are expected to be observed in the second stage.

The second-stage test statistic is where the two methods differ.

Here, the idea is to construct a log-rank test statistic \(L_{Trunc}\) comprised of the data of the

patients who were recruited after the interim analysis, who contribute

to the test statistic in the usual way, and the patients recruited

before the interim analysis who have not had an event yet, who

contribute as left (and possibly right) truncated datapoints. In theory,

this is can be achieved by appropriately adjusting \(n_j\) for the respective event timings

\(j\) in the definition of the log-rank

statistic, and in practice, the survival::coxph method can

handle datasets of the aforementioned structure.

Example

In adoptr, trial designs to investigate time-to-event

endpoints can be represented in objects of the class

TwoStageDesignSurvival. These designs consist of slots for

the first stage efficacy and futility boundaries cf and

ce, a slot for the required number of events in the first

stage n1, slots for the spline interpolation points for the

n2 and c2 functions, and a postulated event

rate \(\psi\).

Two things are important to note here: First, the functions

n1 and n2 will return the number of required

events, not the number of recruits that would be required to achieve

this number of events in expectation. Information on the latter is

instead provided in the summary output of a design. Second,

for one-armed trials, n1 and n2 are the

overall number of required events, while for two-armed trials,

n1 and n2 return half of the overall number of

required events. This is analogous to the case with normally distributed

outcomes, where n1 and n2 return the

group-wise sample sizes. However, calling n1 and

n2 the group-wise number of events would be a misnomer, as

the timings of the interim analyses are based on the overall number of

events, and the number of events are unlikely to be exactly equal across

the two groups.

Let us say we want to plan a two-armed trial trial, where we assume an average rate of events of \(\psi=0.7\).

datadist <- Survival(0.7, two_armed = TRUE)The postulated rate of events \(\psi\) is saved in the

DataDistribution object and will be handed down to any

design optimized with respect to this distribution. It will be used to

convert the required number of events \(d\) to the estimated number of required

recruits via \(\frac{d}{\psi}\), but it

has no other uses. All other design parameters are invariant with

respect to the choice of \(\psi\).

Effect sizes for time-to-event trials are formulated with respect to a hazard ratio. For our example, we assume \(\theta=1\) for the null hypothesis, and a point alternative hypothesis of \(\theta=1.7\).

H_0 <- PointMassPrior(1, 1)

H_1 <- PointMassPrior(1.7, 1)Our desired design should have a maximal type I error \(\alpha\leq 0.025\) and a minimum power of \((1-\beta)\geq 0.8\).

alpha <- 0.025

min_power <- 0.8

toer_con <- Power(datadist,H_0) <= alpha

pow_con <- Power(datadist,H_1) >= min_powerexp_no_events <- ExpectedNumberOfEvents(datadist, H_1)

init <- get_initial_design(1.7, 0.025, 0.2, dist=datadist)

opt_survival <- minimize(exp_no_events, subject_to(toer_con,pow_con),

initial_design = init, check_constraints=TRUE)

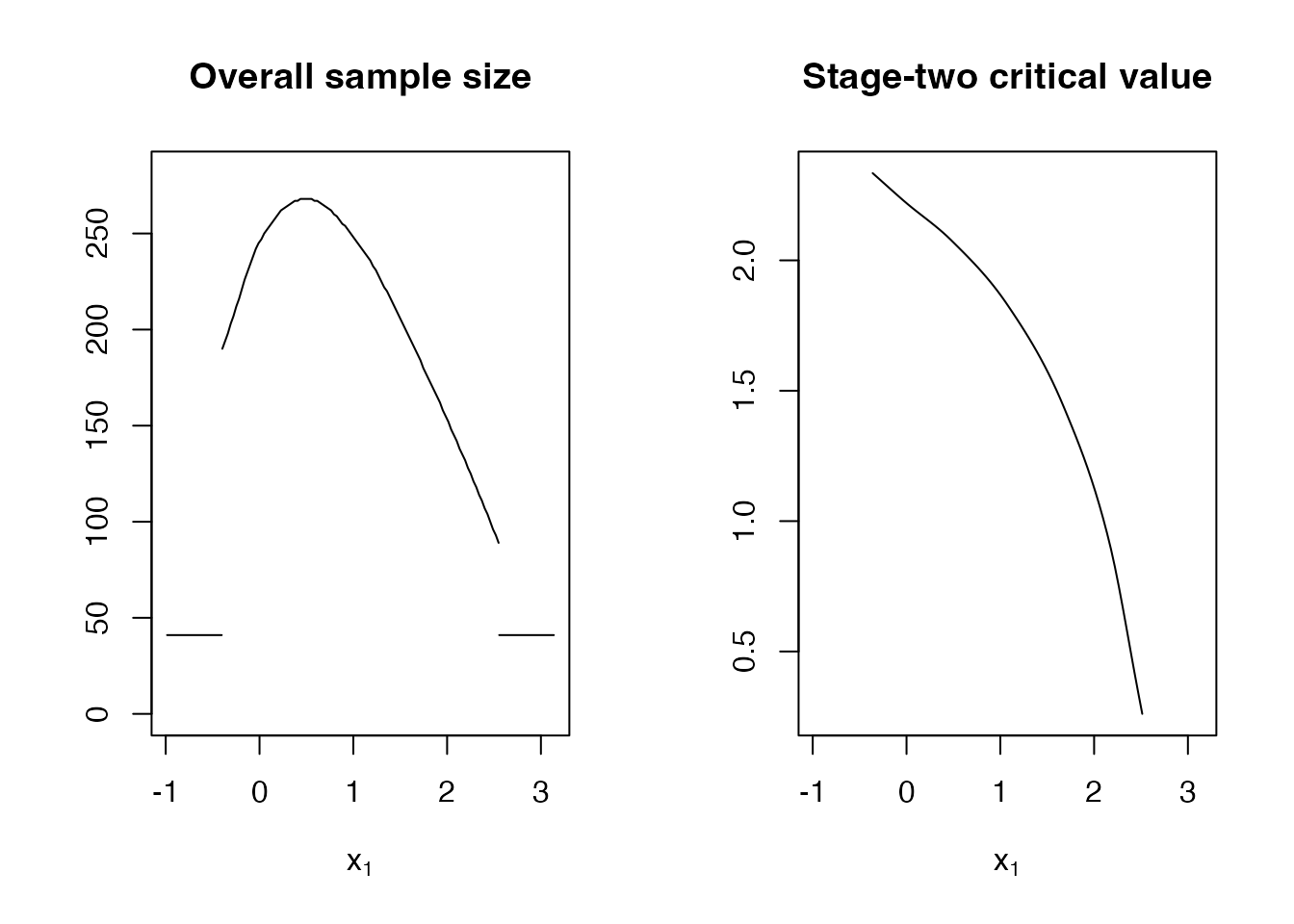

summary(opt_survival$design)

#> For two-armed trials: nevs denotes half of the overall number of required events. nrec denotes the resulting group-wise sample size.

#>

#> TwoStageDesignSurvival: nevs1= 32 --> nrec1= 46

#>

futility | continue | efficacy

#>

x1: 0.79 | 0.83 0.98 1.24 1.54 1.85 2.10 2.25 | 2.29

#>

c2(x1): +Inf | +2.17 +2.02 +1.77 +1.43 +1.00 +0.52 +0.07 | -Inf

#>

nevs2(x1): 0 | 45 42 38 32 24 17 12 | 0

#>

nrec2(x1): 0 | 64 60 54 45 35 25 17 | 0

#> It should be noted that the number of required events \(2\cdot\)nevs1 and \(2\cdot\) nevs2(x1) are the

important information thresholds to be adhered to for testing purposes.

nrec1 and and nrec2(x1) only serve as rough

estimates for the required number of recruits to achieve the target

number of events. If additional information about e.g. time-dependence

of baseline hazards is available, it may be worthwhile to use a more

sophisticated approach than the \(\frac{d}{\psi}\) formula to estimate the

number of required subjects.